I. The Timeless Power of Guernica

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica is far more than just a painting. It is a powerful expression of outrage against war and a lasting symbol of human suffering. Created in response to the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, the work goes beyond the canvas to explore deeper themes of violence, fear and the resilience of the human spirit.

Rather than simply depicting a single moment, Guernica reflects on the nature of war itself. It brings together historical reflection, philosophical inquiry, and artistic innovation in one unified statement. This article offers a closer look at the painting’s background, Picasso’s creative process and techniques, the meaning of its visual elements, interpretations by critics, and the broader impact the work has had in art and society. Through this, we can better understand why Guernica still speaks so strongly to audiences today.

II. A Turning Point in History: The Bombing of Guernica

A. The Spanish Civil War and Political Background

In the 1930s, Spain was deeply divided. Between 1936 and 1939, the country was torn apart by civil war, fought between the elected Republican government and the Nationalist forces led by General Francisco Franco. This conflict was more than an internal struggle. It became a battleground for competing ideologies, with fascism spreading rapidly across Europe. Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy both offered military support to Franco, seeing Spain as a key front in their political ambitions.

Guernica, a small town in the Basque Country of northern Spain, held special significance for the Basque people. It was a centre of their cultural identity and democratic ideals. Although not directly part of the front lines, the town had strategic value as a communications point for the Republicans. Its location made it crucial in the defence of Bilbao, a major city and industrial centre. For Franco’s forces, capturing Bilbao was essential to ending the war in the north, which made Guernica a target.

B. Strategic and Symbolic Importance

Guernica’s value was both military and symbolic. To the Nationalists, it was a stepping stone to Bilbao. To the Basques, it represented autonomy and resistance. The town was home to the Tree of Guernica, a traditional symbol of Basque independence, and the site of the Basque Parliament.

Many Basque citizens opposed Franco’s authoritarian regime, and Guernica came to represent their will to resist. An attack on the town was not only a military act but also a deliberate blow to morale, meant to crush the spirit of a people fighting for freedom.

C. The Attack: What Happened on 26 April 1937

On the afternoon of Monday, 26 April 1937, Guernica was heavily bombed by German and Italian warplanes, acting in support of Franco’s forces. The operation, known as “Operation Rügen”, lasted over three hours. Around 100,000 pounds of explosives and incendiary bombs were dropped, destroying most of the town.

That day was market day, and Guernica was filled with civilians from surrounding villages. The early bombing was relatively light, possibly intended to drive people indoors. This was followed by intense bombing runs that flattened buildings and trapped those inside. People who tried to flee were shot at from low-flying planes.

Approximately 70 per cent of Guernica’s buildings were destroyed. Of the town’s 5,000 residents, about one-third were either killed or wounded. Fires burned across the ruins for days afterwards. Notably, key military targets outside the town, such as bridges and roads, were left untouched. This suggests that the goal was not tactical victory, but terror. Many historians now see this bombing as an early use of psychological warfare, aimed at breaking the population’s will.

The attack also disrupted Republican troop movements and helped the Nationalists to take Bilbao shortly afterwards. Local defenders, overwhelmed by the destruction, were unable to resist further.

D. The Global Response and the Debate That Followed

The bombing of Guernica was one of the first times in modern history that civilians were deliberately targeted in such a way. News of the attack caused international outrage. Although Franco and Hitler denied attacking civilians and claimed they had aimed at military targets, eyewitness accounts and the extent of the destruction tell a different story.

Estimates of the number of deaths have varied. The Basque government originally reported over 1,600 deaths, but later research by local historians places the figure between 170 and 300. Even at the lower end, the human cost was severe, and the act was widely condemned.

Many historians believe the bombing was used to test German aerial tactics, later applied in the Second World War. George Steer, a British journalist reporting for The Times, provided a vivid account of what he witnessed. His report revealed the deliberate nature of the attack and helped turn international opinion against Franco’s forces.

In the years that followed, Guernica came to symbolise the suffering of innocent people caught in the violence of war. In 1997, to mark the 60th anniversary of the bombing, German President Roman Herzog issued a formal apology on behalf of the German people. Today, the bombing is remembered not only as a tragedy but as a turning point in the history of modern warfare.

III. From Grief to Canvas: Picasso’s Creative Journey

A. First Response and the Shift in Focus

At the time of the bombing, Pablo Picasso was living in Paris. He had already been commissioned by the Spanish Republican government to create a mural for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair. His early sketches were focused on quieter, more personal themes, including scenes of his studio.

Everything changed when Picasso read about the bombing in the newspapers. George Steer’s article in The Times had a deep emotional impact on him. Encouraged by the poet Juan Larrea, Picasso abandoned his original idea and began work on a new painting directly inspired by the tragedy in Guernica. He began the piece around 1 May 1937.

The event marked a turning point in his art. Instead of focusing on private or symbolic subjects, Picasso now took on a political message. Guernica would become his most direct and powerful statement on the horrors of war.

B. Artistic Method and the Grisaille Technique

Picasso worked on a monumental canvas, about 3.5 metres high and almost 8 metres wide. He wanted the painting to have an overwhelming effect on the viewer, pulling them into its dramatic scene.

He used a traditional painting method known as grisaille, where only shades of grey, black and white are used. This technique gave the work a sculptural feel and echoed the black-and-white newspaper images through which he had first learned about the bombing. The limited palette also helped convey the sombre mood and emotional weight of the event.

The canvas itself was made from rough jute, primed with lead white and graphite to add texture. Picasso used matte paints to reduce shine and reinforce the serious tone.

Throughout the painting, he used fragmented forms, shifting perspectives and distorted figures, all key features of his Cubist style. These helped to express the confusion, chaos and violence of the bombing powerfully and immediately.

Although the painting is vast and complex, Picasso completed it in less than a month. He produced hundreds of sketches beforehand. American artist John Ferren helped prepare the canvas, and Dora Maar, Picasso’s partner at the time, documented the painting process in photographs. Her black-and-white images may have influenced Picasso’s choice of colours. The result is a work that communicates horror and humanity with clarity and force.

C. Early Sketches and Changing Ideas

To prepare for Guernica, Picasso made over 30 studies and sketches. The earliest ones, drawn soon after the bombing, shifted away from his earlier peaceful scenes and focused on suffering and death. Some sketches explored individual figures, like the horse and the bull, which would become central to the final composition.

It is likely that Picasso was inspired by Francisco Goya’s The Second of May 1808 and may have considered a three-part structure. Early versions of the painting included symbols like a clenched fist and red tears, which he later removed. These changes show how deeply he engaged with the subject and how carefully he thought about the meaning of each detail.

By removing political symbols, Picasso focused on something more universal. Rather than calling for a specific political response, he created a work that expresses the shared pain of war and the deep emotional cost of violence.

- Timeline of Major Events Related to Guernica

Date | Event |

1936 | Outbreak of the Spanish Civil War |

26 April 1937 | Bombing of Guernica |

1 May 1937 | Picasso begins work on Guernica |

12 July 1937 | Guernica was unveiled at the Spanish Pavilion, Paris International Exhibition |

1939–1981 | Guernica exhibited in Europe and the US, on long-term loan to MoMA, New York |

1981 | Guernica returned to Spain |

IV. A Symphony of Symbols: Reading the Visual Narrative

A. The Bull: Brutality, Identity and Ambiguity

The bull is one of the most debated elements in Guernica. It appears on the left side of the canvas, towering over a grieving woman holding a child. Bulls were a recurring motif in Picasso’s work, particularly in his bullfighting scenes, and here it takes on multiple layers of meaning.

Some critics interpret the bull as a symbol of brutal force, possibly representing Franco’s regime or the violent nature of war itself. Others view it as a representation of the Spanish people, their cultural identity, or even Picasso himself. Its emotionless, somewhat detached expression leaves space for interpretation. Rather than giving a clear answer, Picasso seems to invite the viewer to reflect on what the bull means in the context of destruction and suffering.

B. The Horse: Agony and Resistance

At the centre of the painting is a screaming horse, impaled by a spear or sword. It is often seen as the emotional core of the composition. Its wild eyes and flared nostrils convey terror and pain. Some readings suggest the horse stands for innocent victims of war, the citizens of Guernica, or more broadly, the suffering of humanity.

A subtle skull shape appears in the horse’s body, and its mouth gapes open in a silent scream. Originally, Picasso drew the horse with its head lowered, but in the final version, it is raised, straining upward in pain. This shift might signal not only agony but also resistance, a refusal to submit completely to violence.

C. The Weeping Women: Grief, Loss and Universal Mourning

Several female figures in Guernica embody the human cost of war. One clutches her dead child, echoing the traditional Pietà found in religious art. Another woman screams towards the sky, arms stretched wide. A third emerges from a burning building, holding a lamp.

Their distorted faces and knife-like tongues amplify the sense of anguish. These women symbolise not just personal grief but a broader, almost universal cry of pain. By emphasising maternal suffering and emotional devastation, Picasso highlights the everyday consequences of political violence.

D. Light and Darkness: A Fragile Balance

Above the central scene hangs a lightbulb shaped like an eye or a sun. Its rays cast sharp lines across the canvas, adding to the tension. Interpretations vary. some say it represents the watchful eye of God or a symbol of enlightenment, while others link it to the harsh glare of modern technology used for destruction.

The contrast between light and dark in the painting is intense. There is no natural light, no comforting shadows, only sharp edges and stark contrasts. The electric light seems cold and unfeeling. It suggests that even human progress, when misused, can contribute to terror rather than hope.

E. Other Details: Symbols of Despair and Fragile Hope

Beneath the horse lies a fallen soldier, his body broken, his sword shattered. In his hand, a tiny flower sprouts, a small yet powerful symbol of hope amid destruction.

A faint dove, traditionally a symbol of peace, appears hidden and almost erased in the background. The message is clear: peace, if it exists at all in war, is fragile and fleeting.

Newspaper fragments are also integrated into the composition. This references both the source through which Picasso first learned of the bombing and the role of media in shaping our understanding of conflict.

Every detail in Guernica works on both visual and symbolic levels, offering a complex language of suffering, fear and resilience.

- Interpretation of Major Symbols in Guernica

Symbol | Common Interpretation |

The bull | Franco’s fascism, brutality, the Spanish people, or Picasso himself |

The horse | Innocent victims of war, the citizens of Guernica, the suffering of Spain |

The weeping woman | Motherhood, loss of innocent life, universal sorrow |

Lightbulb / Lamp | Eye of God, gaze of Franco, destructive force of modern technology |

Fallen soldier with broken sword | Defeat, the futility of traditional resistance |

The flower | Hope amid destruction |

The dove (or pigeon) | Fragile peace |

V. War, Ethics and Meaning: Philosophical Reflections

A. A Statement Against Fascism

Guernica is widely regarded as one of the most powerful anti-war works of the twentieth century. Its focus on civilian suffering, rather than battle scenes or military victory, set it apart at the time. Picasso openly condemned fascist regimes, and Guernica became his most direct political statement.

While the painting responds to a specific event, its message goes beyond time and place. It speaks to the cruelty of violence, the loss of innocence, and the betrayal of humanity. Its symbols are broad enough to resonate with different conflicts and generations.

The figures in Guernica scream, collapse and burn. But among the horror, there are signs of survival: the raised horse, the blooming flower, the woman holding a lamp. These details suggest that even in darkness, human beings can resist, endure and carry forward.

This tension between despair and resilience makes Guernica more than a protest. It becomes a portrait of the human condition, caught between destruction and the will to rebuild.

B. A Philosophical Perspective on Witnessing and Responsibility

Guernica does not show a specific person or narrative. Instead, it creates a space where viewers are asked to confront violence and reflect on their role, as observers, as citizens, and as human beings.

It challenges us not to look away. In doing so, it becomes a kind of moral mirror, inviting viewers to examine how societies allow atrocities to happen, and what responsibility we share.

Art historians have also noted that Guernica helps us think about how history can be represented. Picasso’s abstraction, his use of symbol and form, shows that artistic truth can sometimes express emotional reality more clearly than a documentary image. It is not a literal record, but a deeply human response to inhuman events.

VI. Critical Voices: Art Historians and Public Reactions

A. First Reactions and Early Debate

When Guernica was first shown at the 1937 Paris International Exhibition, the response was mixed. Some visitors were struck by its emotional power, while others found its imagery confusing or even disturbing. Its lack of colour and non-traditional style set it apart from other works in the Spanish Pavilion.

The painting sparked political discussions as well. Supporters of the Republican cause praised it as a bold condemnation of fascism, while others criticised it for being too abstract or not direct enough in its message. Some were unsettled by the absence of a clear villain or hero.

These divided reactions highlight how far Guernica pushed the boundaries of what political art could look like. It was not designed to offer comfort or clear answers, but rather to challenge viewers and provoke thought.

B. Symbolism and Guernica as a Modern History Painting

Over the years, critics and historians have proposed many different readings of the painting’s symbols. The bull, horse, women, and light sources have all been analysed in multiple ways, depending on the context and period.

Picasso’s use of Cubist structure and the grisaille palette has also received close attention. The limited colour scheme reinforces the mood of mourning, and the broken composition mirrors the fragmented reality of war.

What makes Guernica so enduring is that it refuses to settle into a single meaning. Each generation finds new relevance in its imagery. It invites continued engagement, analysis and emotional response, which is the mark of a truly living artwork.

Traditionally, history paintings depicted battles, heroic deeds or grand figures. Guernica broke with that tradition. It focused not on victory but on suffering, not on rulers but on ordinary people caught in tragedy.

For this reason, many consider it one of the first truly modern history paintings. It captures a moment in time, but it also speaks to larger truths about power, pain and resistance. Over the decades, it has appeared in protests, exhibitions, and documentaries, constantly renewing its voice in new political and cultural settings.

Its presence has become a form of resistance in itself, a quiet but powerful reminder of what happens when violence goes unchecked.

VII. Guernica in Dialogue: Comparing Other Works

A. Picasso’s Related Works

Guernica represents a turning point in Picasso’s career. Compared to his earlier Cubist works, which focused more on abstract form, Guernica is rooted in a specific historical context and tells a powerful narrative.

Following Guernica, Picasso created the Weeping Woman series, which can be seen as a more personal and emotionally focused exploration of the same themes of grief and suffering. These works delve deeper into the sorrow expressed in Guernica, giving it a more intimate voice.

There are also important connections to Picasso’s earlier depictions of bullfighting scenes, where bulls and horses often appear as recurring symbols. His 1935 etching Minotauromachia is particularly significant — many see it as a direct forerunner to Guernica, as it brings together several of the same symbolic elements in a compressed, emotionally charged form.

Understanding Guernica within the broader arc of Picasso’s artistic development reveals his consistent interest in political subjects and his use of powerful symbolism. It shows how Guernica was not a sudden departure, but the culmination of themes he had long been exploring.

B. Responses by Other Artists

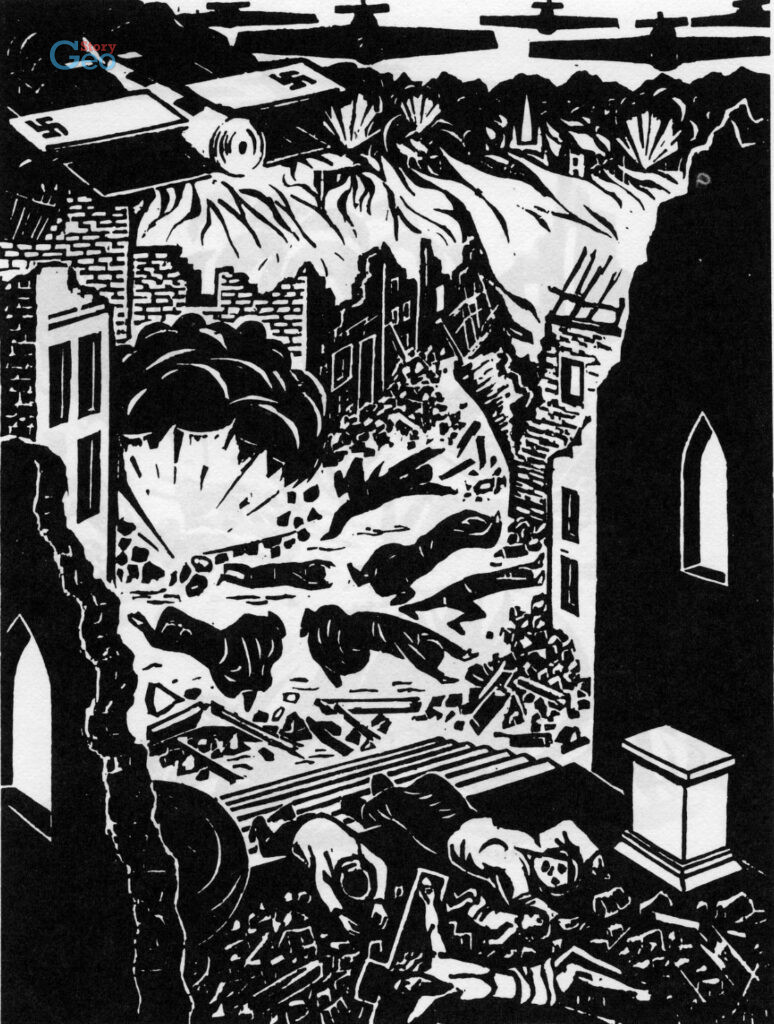

Many artists have responded to the bombing of Guernica through their work. For instance, Heinz Kiwitz created a woodcut titled The Bombing of Guernica, while René Magritte painted The Black Flag. Both pieces show how artists used striking imagery to protest violence, echoing Picasso’s approach.

Picasso’s message in Guernica shares common ground with Francisco Goya’s powerful print series The Disasters of War, which also revealed the horrors of conflict. Decades later, artists like Leon Golub and Rudolf Baranik drew on similar themes and visual styles to protest the Vietnam War.

Other works, such as The Keiskamma Guernica in South Africa and African Guernica by Dumile Feni, take inspiration from Picasso’s painting but focus on different struggles. These artists used the familiar composition of Guernica to address injustice and suffering in their societies.

Seen in this broader context, Guernica stands out as a turning point in modern art. It has inspired generations of artists around the world to raise their voices through art against war, violence and social injustice.

- Comparison of Guernica and Other Works by Picasso

Title of the Work | Key Stylistic Features | Main Themes | Relation to Guernica |

Guernica | Cubist forms, monochrome palette, monumental scale | Horrors of war, suffering, resistance | A direct response to a historical event, conveying a powerful political message |

Early Cubist Works | Fragmentation of form, multiple viewpoints, abstract tendencies | Analysis and reinterpretation of subjects | Uses abstract forms but lacks specific historical narrative |

Weeping Woman Series | Distorted figures, strong colour (in some), emotional intensity | Grief, pain, loss | Expands on the motif of sorrow introduced in Guernica |

VIII. The Ongoing Legacy: Impact and Relevance

A. Display History and Public Response

Guernica was first shown at the 1937 Paris Expo, where it stood out for its raw emotion and unconventional form. After the exhibition, it travelled widely, raising funds for Spanish refugees and bringing attention to the civil war.

During the Second World War and afterwards, it remained in the care of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, where it stayed for decades. Picasso made it clear that the painting should not return to Spain until democracy had been restored. That moment finally came in 1981, six years after Franco’s death, when Guernica was moved to Madrid. It is now housed in the Museo Reina Sofía, where it continues to attract visitors from around the world.

Public reactions have evolved over time. While the work once shocked some viewers, it is now recognised as a masterpiece and a symbol of political courage. Its journey reflects not only the history of Spain, but also a changing global awareness of the power of images to influence thought.

B. Influence on Art, Society and Politics

Guernica has left its mark far beyond the museum walls. It has appeared on posters, protest banners and in classrooms. Its use of universal symbols makes it a natural point of reference for other artists dealing with trauma, injustice or war.

In political settings, the painting has also played a role. A famous example occurred in 2003 at the United Nations, when a tapestry replica of Guernica was covered during a press conference where US officials discussed military action in Iraq. The image was considered too powerful and potentially distracting, a clear sign of its ongoing relevance.

Art documentaries, scholarly essays and public debates continue to explore Guernica, not as a finished object of the past, but as a living work that raises questions about morality, memory and responsibility.

Its influence shows no sign of fading. In a world still marked by conflict, Guernica continues to speak with urgency and grace.

IX. The Enduring Echo of Guernica

This article has explored Guernica from its historical roots to its modern impact. Born out of tragedy, the painting stands as a landmark in the history of art and human expression.

It brings together powerful visuals, emotional weight and timeless symbolism to deliver a clear message: that violence leaves lasting scars, and that art must bear witness. Picasso’s genius lies not only in his technique but in his ability to transform horror into a form of truth that cannot be ignored.

Today, Guernica still calls to us, not only as a memory of a particular time and place, but as a reminder of the costs of silence, the fragility of peace and the resilience of the human spirit.

It asks us not to look away. And more than that, it asks us to care.

Guernica

Pablo Picasso (Pablo Ruiz Picasso)

Malaga, Spain, 1881 – Mougins, France, 1973

- Date: 1937 (1st May – 4th June, Paris)

- Technique: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 349,3 x 776,6 cm

- Category: Painting

- Entry date: 1992

- Observations: The government of the Spanish Republic acquired the mural “Guernica” from Picasso in 1937. When World War II broke out, the artist decided that the painting should remain in the custody of New York’s Museum of Modern Art for safekeeping until the conflict ended. In 1958 Picasso extended the loan of the painting to MoMA for an indefinite period, until such time that democracy had been restored in Spain. The work finally returned to this country in 1981.

- Register number: DE00050

- On display in: Room 205.10 – Guernica

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía