I. The Dawn of a Revolution: The Birth of Cubism

A. Breaking from Tradition: Post-Impressionist Roots and the Influence of Cézanne

In the early twentieth century, the art world was undergoing a radical transformation. Many artists were moving away from long-held conventions, searching for new ways to express a rapidly changing world. While Impressionism focused on the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, Cubism emerged as a bold visual language that redefined the very foundations of painting.

For centuries, Western art had relied on tools such as linear perspective and chiaroscuro to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. Cubism challenged this entire tradition, rejecting the idea that painting should imitate nature from a single, fixed viewpoint.

At the centre of this shift was the profound influence of Paul Cézanne. Widely regarded as a key forerunner of Cubism, Cézanne’s later work explored the simplification of form into planes and volumes. Through repetitive brushwork and subtle shifts in perspective, he examined objects from multiple angles, anticipating the core principles of Cubism. His famous statement that everything in nature is made according to the sphere, the cone and the cylinder had a lasting impact on Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Cézanne’s structural approach helped lay the groundwork for Cubism’s earliest experiments. His vision of reducing nature into geometric shapes and his interest in observing form analytically provided Picasso and Braque with the conceptual tools they needed to begin building a new visual language.

In 1908, art critic Louis Vauxcelles mockingly described Braque’s Houses at L’Estaque as being composed of little cubes. Though the term was dismissive, the label Cubism stuck. Braque’s geometric landscape, inspired by Cézanne, signalled a break from traditional perspective and hinted at a new way of seeing.

Cubism grew out of this desire to capture complexity, not through illusion but through structure. It marked a turning point where artists no longer felt bound by the rules of Renaissance space. Instead, they embraced multiplicity, showing us not just what we see but how we see it.

B. Embracing the Primitive: The Catalytic Role of African and Iberian Art

Picasso’s creative evolution was not limited to the traditions of European painting. His encounter with African and Iberian art would revolutionise his visual language and challenge the aesthetic values of the Western canon.

In 1907, a visit to the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris left a profound impression on him. There, Picasso encountered African masks and sculptures that he did not see as decorative art, but as powerful, mystical objects, weapons as he described them, for warding off unknown forces. These works, with their raw energy and spiritual presence, gave Picasso a new understanding of what art could express.

This influence is most clearly visible in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, particularly in the mask-like faces of the two women on the right. Their sharp, angular forms reflect not only African visual language but also a departure from naturalism.

Alongside African art, Iberian sculpture, especially artefacts excavated at Osuna and Cerro de los Santos, offered Picasso a vision of art before the influence of classical civilisation. These ancient figures, direct and unrefined, validated his move away from academic beauty and supported his search for more primal forms of expression.

Picasso’s engagement with so-called primitive art was more than a stylistic choice. It was a philosophical statement. By incorporating non-Western visual elements into Cubism, he challenged the Eurocentric hierarchy of art history. He suggested that expressive power and artistic truth could be found far beyond the classical tradition.

In doing so, Picasso helped open the door for 20th-century modernism to draw inspiration from global cultures. Where Western painting had long prioritised harmony and idealised form, Picasso sought to purge painting of what he called the deadening habits of convention, to strip away imitation and illusion, and uncover something more essential.

This refusal of mimicry and rejection of perspective as a given would become central to Cubism’s aesthetic. It reshaped how modern artists thought about representation, truth and cultural value.

C. Sparks of Collaboration: The Joint Journey of Picasso and Braque

While Picasso is often credited as the driving force behind Cubism, its evolution was shaped by one of the most significant partnerships in modern art. From late 1907, he and Georges Braque entered into a close artistic exchange that would fundamentally transform their work and the direction of early twentieth-century painting.

Working side by side in Montmartre and later in the south of France, Picasso and Braque engaged in a rigorous visual dialogue. They shared studios, studied each other’s canvases and pushed one another to refine their formal discoveries. Braque once described their relationship as being like mountaineers roped together, exploring the unknown. It was a partnership built not only on shared ambition but on mutual trust and intellectual challenge.

Their collaboration marked a period of intense experimentation. Together, they broke away from traditional perspective and chiaroscuro, replacing depth with shallow space, volume with flattened planes, and fixed viewpoints with multiple angles. They stripped their compositions of decorative elements, instead favouring subdued palettes of greys and ochres that focused attention on form.

This ongoing exchange between the two artists resulted in an unprecedented rate of innovation. Their work became so closely aligned during this phase that at times it is difficult to distinguish one hand from the other. But more importantly, their dialogue propelled Cubism forward with a coherence and clarity that would not have been possible in isolation.

Cubism was not merely the product of individual genius but of an intellectual partnership that redefined how art could represent the world. It stands as a testament to the power of collaboration in reshaping the language of modern painting.

D. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon: A Declaration of Proto-Cubism

Among the many turning points in Picasso’s career, ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ remains one of the most shocking and influential. Painted in 1907, it marked the beginning of a new approach to visual form, breaking sharply with artistic tradition and laying the groundwork for what would become Cubism.

The painting presents five nude women in a brothel, depicted not with naturalistic softness but with harsh angularity and fractured space. Their bodies are twisted and flattened, their features mask-like and confronting. The two figures on the right draw from African sculpture, while the rest reflect Picasso’s interest in Iberian art. There is no unified space or consistent perspective; instead, the viewer is confronted with a collision of forms, as if seen from multiple angles at once.

This rejection of classical ideals was not merely formal. The painting challenges the viewer directly, both in subject and in style. Gone is the detached, idealised gaze of traditional nudes. These women stare out with sharp intensity, asserting their presence and collapsing the distance between viewer and subject.

‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ was so radical that Picasso hesitated to show it publicly. Even his close friend Henri Matisse reportedly reacted with horror. The painting remained unseen until 1916, yet by then its influence had already begun to ripple through the avant-garde.

While the term Cubism had not yet been coined, the painting introduced many of its key innovations: the fragmentation of space and form, the integration of non-Western aesthetics, and the rejection of illusionistic depth. It is rightly seen as the manifesto of a new vision, one that reimagined the role of painting in the modern world.

II. The Two Faces of Cubism: The Dialectic of Analysis and Synthesis

A. Analytic Cubism: The Deconstruction of Form and the Multiplicity of Viewpoints

Analytic Cubism, which spanned roughly from 1908 to 1912, is characterised by the dissection of objects into fragmented geometric planes and the reconstruction of those forms from multiple viewpoints. During this phase, artists sought to examine and understand a subject not from a single perspective but through a simultaneous display of several angles.

This approach rejected the traditional linear perspective and created surfaces that seemed abstract or shattered. The compositions often gave the impression of light bouncing off broken mirrors. Forms were typically concentrated in the centre of the canvas and gradually dispersed towards the edges, contributing to an overall sense of controlled disintegration.

Between 1910 and 1912, Picasso explored portraiture in this mode, reducing faces and bodies into overlapping, faceted shapes. A single head might be rendered to show the front and profile views at once, merging spatial and temporal perceptions in one surface.

This fragmentation was more than a stylistic innovation. It was a visual response to contemporary intellectual shifts, especially the rise of the theory of relativity and new conceptions of the fourth dimension. By rejecting fixed perspectives, Cubism aimed to depict reality as dynamic and ever-changing. Analytic Cubism’s multiple viewpoints and structural dislocations challenged the idea of a singular, objective reality.

Picasso’s use of simultaneous perspectives and layered spatial planes reflected an interest in the complexity of perception and the continuity of space and time. In this way, Analytic Cubism became a visual analogue to scientific inquiry, suggesting a profound link between early modernist art and contemporary theories of knowledge and reality.

B. A Restrained Palette: Focusing on Form

One of the defining features of Analytic Cubism is its subdued colour palette. Artists deliberately limited themselves to muted tones such as greys, ochres, browns, creams, greens and blues. These reduced chromatic choices ensured that colour did not distract from the structural concerns of the composition.

The suppression of vivid colour accentuated the flatness of the picture plane and diminished the illusion of depth. Shadows were often used to create shallow bas-relief effects, but the overall impression was one of a flattened surface and compressed space.

This intentional limitation of colour was a strategic choice, reflecting the intellectual rigour of the movement. It encouraged viewers to concentrate on the dissection and reconstruction of form rather than being seduced by decorative elements. The monochromatic restraint reinforced the cerebral nature of Analytic Cubism, underscoring its focus on structural relationships rather than surface appeal.

A representative female portrait from this period is Woman with a Mandolin (1910). This work is a classic example of Analytic Cubism, characterised by geometric fragmentation, overlapping planes and a restrained palette. The figure and the instrument are abstracted almost beyond recognition, drawing the viewer into an intellectual engagement with the interaction of form and meaning.

C. Synthetic Cubism: Reconstructing a New Reality through Collage

From around 1912 onward, Picasso and Braque began to shift away from the highly abstract language of Analytic Cubism. This transition marked the birth of Synthetic Cubism, a more playful and expansive phase in which colour returned, and forms grew larger and more decorative.

Synthetic Cubism sought not to analyse objects but to construct them anew. The artists deliberately flattened their compositions even further, eliminating any lingering suggestions of three-dimensional space. Instead, they emphasised the surface reality of the canvas itself.

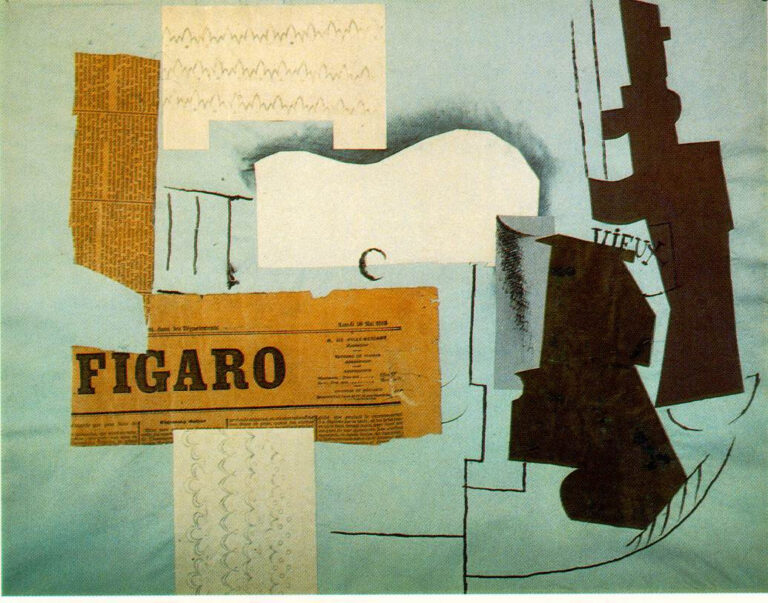

One of the most groundbreaking innovations of this period was the development of collage, particularly the technique known as papier collé. This method, first introduced by Braque and quickly adopted by Picasso, involved pasting real-world materials directly onto the canvas. These materials included newspaper clippings, wallpaper fragments, tobacco wrappers and printed labels.

The inclusion of these everyday items brought texture, humour and an element of surprise to the artworks. Collage blurred the boundary between art and life, questioning the nature of representation and illusion. It also reaffirmed the flatness of the canvas, drawing attention to its two-dimensionality rather than pretending it offered a window onto the world.

Some scholars have noted the gender dynamics implicit in Picasso’s choice of materials. By using wallpaper or cloth patterns traditionally associated with domestic or feminine spaces, he appeared to subvert or incorporate those associations into high art. The act of cutting and pasting was seen by some as echoing traditionally feminine crafts such as dressmaking.

In certain collages, symbolic references to masculinity, such as pipes, beer labels and newspapers, were juxtaposed with floral motifs or decorative prints. These compositions opened space for subtle investigations of gender identity, as well as a broader commentary on the shifting roles of representation and reality.

- The Evolution of Cubist Forms

Category | Proto-Cubism (c. 1907) | Analytic Cubism (c. 1908–1912) | Synthetic Cubism (c. 1912–1914) |

Main Features | Early Cubism | Analytical deconstruction of form | Constructive synthesis of form |

Primary Influences | Cézanne, African art, Iberian sculpture | Cézanne, African/Iberian art, innovation by Braque | Analytic Cubism, collage, Braque’s innovations |

Colour Palette | Moving away from the gloom of the Blue Period, use of ochre, green, red, blue tones (e.g. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon features warm reds and pinks with deep blues) | Limited and restrained palette of black, grey, ochre, brown tones | Brighter and more decorative colour palette |

Form and Structure | Angular and fragmented shapes, distorted figures, geometric composition | Small, tightly interwoven geometric planes, often viewed from multiple angles, dense central areas, highly abstract | Simpler and more decorative forms, shapes are reconstructed and boldly outlined |

Spatial Representation | Flattened, compressed space, break from Renaissance perspective | Dense, ambiguous space, background and figure merge | Emphasis on surface flatness, removal of three-dimensional illusion |

Core Principles | Fragmentation, geometric shapes, early use of sculptural lighting and multiple viewpoints | Visual analysis of the subject, multiple viewpoints, fragmentation, muted tones | Use of collage (papier collé), real materials, bold colour, free use of form |

Representative Works | Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) | Woman with a Mandolin (1910), Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910), Woman’s Head (Fernande) (1909) | Still Life with Chair Caning (1912), Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass (1913), Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (1913) |

III. A Philosophical Canvas: The Enduring Impact of Cubism

A. Challenging Perception: Beyond the Single Viewpoint

Cubism posed a fundamental challenge to the concept of a single, objective reality. By embracing fragmentation and multiplicity, it dismantled the Renaissance tradition of fixed perspective and replaced it with shifting angles and visual distortion. This radical shift reflected broader philosophical and scientific ideas of the early twentieth century, such as the theory of relativity and the notion that our understanding of the world is shaped by relational viewpoints.

Cubist works draw viewers into a space where intention is dispersed and where forms refuse to conform to a singular perspective. The act of viewing becomes active and analytical, requiring the observer to piece together meaning from fragmented forms. Picasso believed that art must reconstruct reality in terms of structure, weight, form and duration.

By compelling viewers to engage with a splintered vision of reality, Cubism nurtured a new mode of perception that mirrored the complexities of modern life. It went beyond passive consumption and demanded intellectual effort. This perceptual and conceptual challenge helped lay the foundation for a more interactive understanding of art, where the viewer’s interpretation becomes an essential part of the work’s meaning.

B. Art as Creation, Not Imitation

One of the most lasting legacies of Cubism was its firm rejection of the idea that art must imitate nature. Picasso held that the act of painting should not be an illusionist exercise but a creative gesture. Rather than reproduce what already exists, he sought to construct an entirely imagined world on the canvas.

To Picasso, the artist was not a passive recorder but a visionary and an inventor of new realities. He viewed the making of art as a kind of ritual act, one that dealt with unseen forces that shape human fate. This emphasis on subjective vision and artistic autonomy was a key feature of Modernism.

Cubism’s insistence that art is an act of invention liberated artists from centuries of imitation and redefined the purpose and potential of painting. This philosophical stance opened the door to abstraction and conceptualism, where the internal vision of the artist and the inherent truth of the artwork became more significant than any likeness to external appearances.

C. The Legacy of Cubism in the 20th Century and Beyond

Cubism stands as one of the most influential visual languages of the twentieth century. It revolutionised the depiction of form and space and cleared a path for abstract tendencies in modernist art.

Its influence extended far beyond painting. Movements such as Futurism, Suprematism, Dada, Constructivism, De Stijl, Abstract Expressionism and even Neo-Expressionism absorbed its core ideas. Cubist principles also found expression in sculpture, architecture and graphic design.

Cubism’s legacy endures in part because it embraced a critical tension at the heart of modernism, a scepticism towards representation and a bold confidence in reinvention. Its radical approach to perception, structure and composition provided a launch point for many of the major artistic innovations that followed.

By redefining visual language through fragmentation, multiple viewpoints and the integration of diverse materials, Cubism offered a new way of seeing and making. It remains a foundational movement that shaped the direction of modern art and continues to inform contemporary practices across disciplines.

V. Picasso’s Cubist Vision

Picasso’s journey through Cubism began with the structural influence of Paul Cézanne and the profound impact of African and Iberian art. From these foundations, he developed the movement through two distinct phases, Analytic Cubism and Synthetic Cubism, each of which redefined the nature of artistic creation.

Throughout this evolution, Picasso played a central role, continuously pushing the boundaries of what art could express. His work within Cubism did not simply reshape visual language; it altered the way we perceive and engage with form, space and meaning. By challenging established ideas of representation and authorship, Cubism transformed artistic thinking at its core.

It was more than a style. Cubism emerged as a philosophical approach to making and understanding art, one that played a defining role in shaping the direction of 20th-century aesthetics. It gave artists a new visual vocabulary and offered a conceptual framework that extended far beyond painting.

Picasso’s relentless pursuit of innovation and his ability to reshape his visual language again and again stand as lasting evidence of his creative force. The legacy of Cubism, shaped so profoundly by his vision, remains alive in the practice of contemporary art today.